by Alan Langstaff

Well, another year is soon coming to an end. Thanksgiving is here, and Christmas comes next.

But first, let’s look at Thanksgiving. I grew up in Australia, where we did not have a Thanksgiving Day in November. It is not that we weren’t thankful, it is that we didn’t have a public holiday to celebrate it. Since coming to America 45 years ago, I have come to appreciate Thanksgiving. It is the least commercialized holiday of the year. It is a time to thank God for all His blessings, to get together as a family, and enjoy a Thanksgiving meal. I especially like the turkey.

In looking at Thanksgiving and from preaching about it in church, I have generally centered on the story of the first Thanksgiving that the pilgrims celebrated, which is a wonderful story.

But as I have learned more about American history, I have discovered more about the events of Thanksgiving.

I came across an article in the Minneapolis Star Tribune entitled “A unifying holiday, born in discord” by Ted Widmer. Here is part of that article.

“Thanksgiving arrives just when we need it – our most unifying holiday, at one of the most divisive moments in recent American history.

In general, the holiday is celebrated the same way around the country, which is among its best qualities. There are no blue-state versions and red-state versions. We all experience roughly the same routine as we go in and out of the annual food coma, punctuated by sidelong glimpses at football games and floating Snoopys on TV.

We all sit at tables with distant relatives and stragglers, breaking bread together.

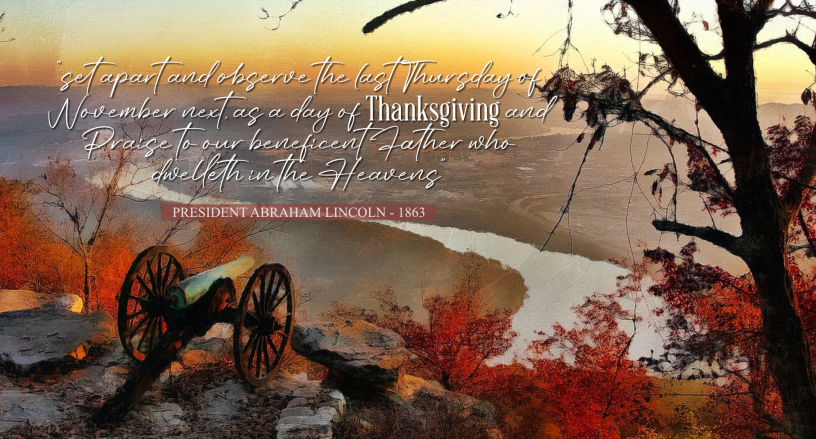

That national sameness was very much a goal of the holiday’s architects, who created it at an even more divisive moment. With the Civil War raging in 1863, President Abraham Lincoln and his secretary of state, William Seward, issued a proclamation on Oct. 3 calling for a national holiday to be observed on “the last Thursday of November.”

That proclamation, a document of unusual literary grace, might do good service again in a nation that could use words of healing…”

Thanksgiving in those days was celebrated all over the country, with the dates of Thanksgiving set by the different States. There was no national Thanksgiving Day.

“Part of the problem was that the South distrusted a holiday tied to the early history of New England. Thanksgiving conjured images of the Pilgrims, a connection that was consciously promoted by a crusading journalist, Sarah Josepha Hale, who edited a popular women’s magazine, Godey’s Lady’s Book. Hale had been advocating for a Thanksgiving holiday for decades (she also wrote “Mary Had a Little Lamb”). But she vexed Southern politicians with her anti-slavery writings, and many Southern governors, like Henry Wise of Virginia, refused to have anything to do with her precious holiday.”

Lincoln was greatly helped by Seward, with whom he had forged a great partnership, including acts of unity.

“In the fall of 1863, Seward saw an opening. After two years of brutal fighting, the tide had turned, with Union victories the previous summer at Vicksburg and Gettysburg. That was reason enough to give thanks.

But what if the president issued a sweeping proclamation that gave thanks on behalf of the entire American people, including those who were at war against the United States? That would be creative statecraft, reminding Americans that they remained a single people.”

What can we learn from the historical records of the Thanksgiving Day Proclamation?

1) Even though the circumstances of the times were somewhat bleak, we can always find something to be thankful for. The Psalms can give you inspiration.

The old chorus “Count your blessings / name them one by one / and it will surprise you / what the Lord has done.”

2) Thanksgiving Day Proclamation was given at a dark time in our nation of America. The North and the South had been fighting the Civil War. How could one be thankful in the midst of such conflict? Nonetheless, Lincoln issued the proclamation:

“In places, it has an Old Testament feeling, praising ‘our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the Heavens.” But it also carries a message of charity, more in keeping with the New Testament. Even though huge armies were still clashing in the field, Seward and Lincoln never indulge in self-absorption or braggadocio. Instead, they write humbly of “the blessings of fruitful fields and healthful skies.”

3) It speaks of “unifying” people. There is something about Thanksgiving that draws families and people together. It is a unifying holiday, born in discord, but nonetheless points to a better time to come.

“And in perhaps the most important line, it celebrates one country, not two: “It has seemed to me fit and proper that they should be solemnly, reverently and gratefully acknowledged as with one heart and one voice by the whole American People.”

Now those 3 simple things can be replayed today.

1) We need to be thankful and count our blessings. At the Thanksgiving table, we can ask people to do just that.

2) We can remember that even in dark times, when life seems hard for one reason or another, we can still be thankful.

3) It can be a time of “unifying” when past hurts are forgiven, when grudges can melt away. We can come together to the Lord and thank him together, especially for Jesus who died for us on Calvary’s cross and whose incarnation we celebrate in just a few weeks at Christmas time.